Obesity isn’t just about eating too much or moving too little. It’s a biological malfunction - a system that’s lost its way. Your body has built-in controls for hunger, fullness, and energy use. When those controls break down, weight gain isn’t a choice. It’s a consequence of broken signals. And this isn’t new. Since the discovery of leptin in 1994, we’ve learned that obesity is a chronic disease of the brain and metabolism, not a moral failing.

The Brain’s Hunger Switches

At the center of this is a tiny area in your brain called the arcuate nucleus. It’s like a control room for appetite. Two sets of neurons fight for control: one tells you to stop eating, the other tells you to eat more. The first group, called POMC neurons, release a chemical called alpha-MSH. When this hits the right receptors in your brain, you feel full. Studies show this can cut food intake by up to 40%. The other group, NPY and AgRP neurons, do the opposite. When they fire, hunger hits hard. In lab tests, turning on just these neurons made mice eat 300-500% more in minutes.These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to hormones from your body. Leptin, made by fat cells, tells your brain, ‘I’ve got enough stored.’ In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, they rise to 30-60 ng/mL - but the brain stops listening. That’s not a lack of leptin. It’s leptin resistance. Your brain is drowning in signals but can’t hear them.

Insulin, released after meals, also tells your brain to stop eating. Fasting levels are around 5-15 μU/mL. After eating, they jump to 50-100 μU/mL. But in obesity, insulin’s message gets lost too. Ghrelin, the hunger hormone, does the opposite. It spikes before meals - from 100-200 pg/mL when you’re empty to 800-1000 pg/mL right before you eat. In people with obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop properly after meals, so hunger lingers.

The Broken Wiring Behind the Signals

It’s not just about hormone levels. It’s about how the brain processes them. Leptin and insulin both use the same pathway in the hypothalamus: PI3K-AKT-FoxO1. When this pathway works, it reduces appetite by 30-50%. But in obesity, this pathway gets blocked. In fact, if you block PI3K in a lab, leptin loses its power to suppress hunger completely. That’s how critical it is.Another player is mTOR, a cellular sensor that responds to nutrients. When activated, it tells your brain to eat less. In older mice, stimulating mTOR reversed age-related weight gain. But in obesity, mTOR signaling gets disrupted. Then there’s BMP4, a protein that helps regulate fat. Giving BMP4 to obese mice cut their food intake by 20%. These aren’t side effects - they’re core mechanisms.

And then there’s inflammation. In obesity, the brain’s immune cells get activated. JNK, a stress kinase, turns on and blocks leptin signaling. This creates a loop: more fat → more inflammation → more leptin resistance → more eating → more fat. It’s self-reinforcing. And it’s why losing weight gets harder the longer you’ve carried it.

Other Hormones in the Mix

It’s not just leptin and ghrelin. Pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after eating, slows digestion and reduces hunger. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low - just 15-25 pg/mL instead of the normal 50-100 pg/mL. That means even after eating, the ‘stop’ signal is weak.Estrogen plays a role too. After menopause, women often gain belly fat quickly. Why? Estrogen helps suppress appetite and boosts energy use. When estrogen drops, so does the brake on eating. Studies on mice without estrogen receptors show they eat 25% more and burn 30% less energy. That’s not just lifestyle. It’s biology.

Orexin, a brain chemical linked to wakefulness, is also involved. In obese people, orexin levels drop by 40%. But in night-eating syndrome, they spike. That’s why people with narcolepsy - who have low orexin - are two to three times more likely to be obese. It’s not sleepiness causing weight gain. It’s the same broken signal.

Why Diets Fail - And What Works Instead

Most diets fail because they ignore the biology. You cut calories, your body thinks you’re starving. Leptin drops. Ghrelin rises. Your brain screams for food. Your metabolism slows. You lose muscle. You regain weight - often more than before. That’s not weakness. That’s your body defending its fat stores.But new drugs are changing this. Setmelanotide, a drug that activates the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R), works in rare genetic cases of obesity. In people with POMC or LEPR mutations, it cuts weight by 15-25%. That’s not a miracle. It’s fixing a broken switch.

Then there’s semaglutide. Originally for diabetes, it mimics GLP-1, a gut hormone that tells your brain you’re full. In clinical trials, people lost an average of 15% of their body weight. Why? It doesn’t just reduce appetite. It makes food less rewarding. You still eat, but you don’t crave it the same way.

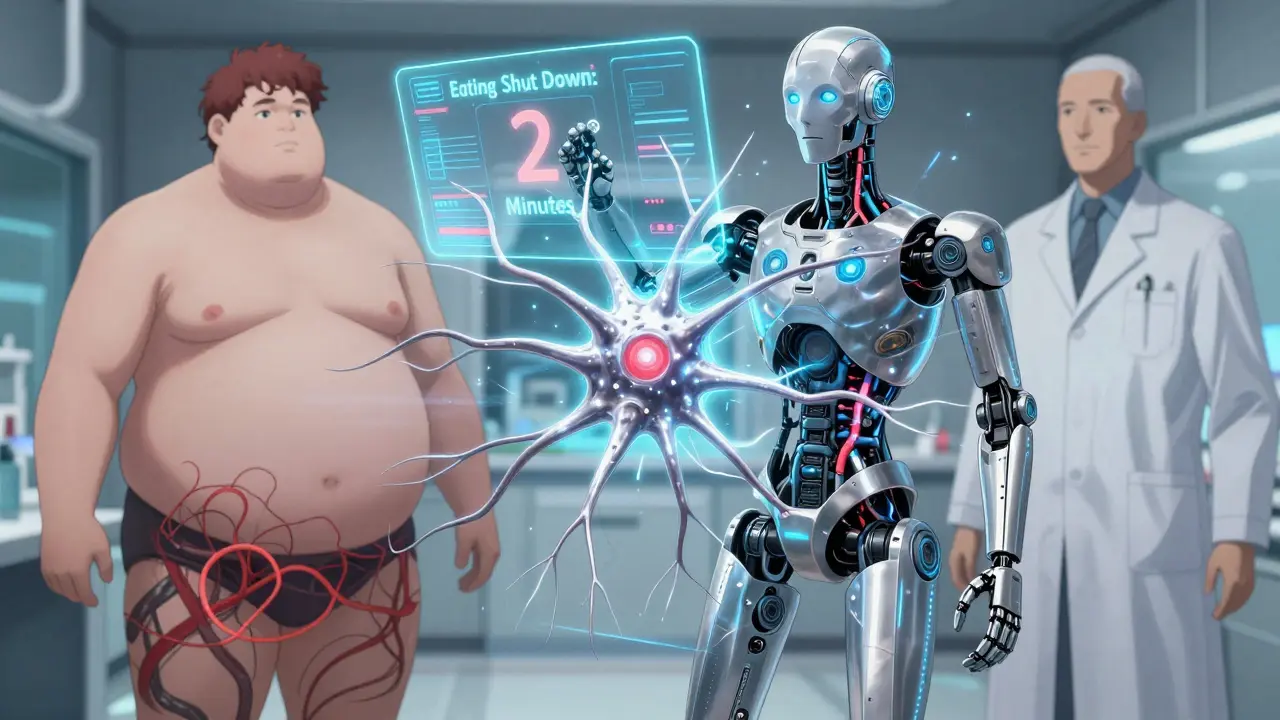

And in 2022, scientists found a new group of neurons right next to the hunger and fullness cells. When activated, they shut down eating within two minutes. This wasn’t known before. It’s a new target. Future drugs may combine GLP-1, MC4R, and these new neurons - hitting multiple pathways at once.

The Bigger Picture

Obesity affects 42.4% of U.S. adults. Globally, rates have nearly tripled since 1975. It’s linked to 2.8 million deaths a year. The U.S. spends $173 billion annually treating its complications. This isn’t a lifestyle issue. It’s a medical crisis rooted in biology.People with obesity aren’t lazy. Their brains are fighting a war they didn’t choose. The body’s systems - appetite, metabolism, reward - are all out of sync. And when you try to fix it with willpower alone, you’re fighting biology with a spoon.

The future isn’t about more diets. It’s about understanding the switches. Leptin resistance. Insulin signaling. Glucagon-like peptides. Melanocortin pathways. These aren’t abstract terms. They’re the real reasons why weight loss is so hard - and why new treatments are finally working.

If you’re struggling with weight, know this: it’s not your fault. Your body isn’t broken because you failed. It’s broken because its signals got lost. And science is finally learning how to fix them.