Ever taken the same pill as someone else and had a totally different experience? One person feels fine, another ends up in the ER. It’s not luck. It’s biology. Medications don’t work the same for everyone - and the reasons why are deeper than most doctors even talk about.

It’s Not Just About the Drug

Most people think side effects are just bad luck. You take a pill, you get dizzy, nauseous, or worse. But that’s not random. It’s your body’s unique reaction to the medicine. Your genes, your age, what else you’re taking, even your gut bacteria - all of it plays a role. The World Health Organization calls these unwanted reactions adverse drug reactions (ADRs). And they’re not rare. In Europe, 3.6% of hospital admissions are caused by them. In the UK, ADRs cost the NHS £770 million every year. That’s not just a statistic - it’s people getting sick from medicines meant to help them.Your Genes Are the Main Player

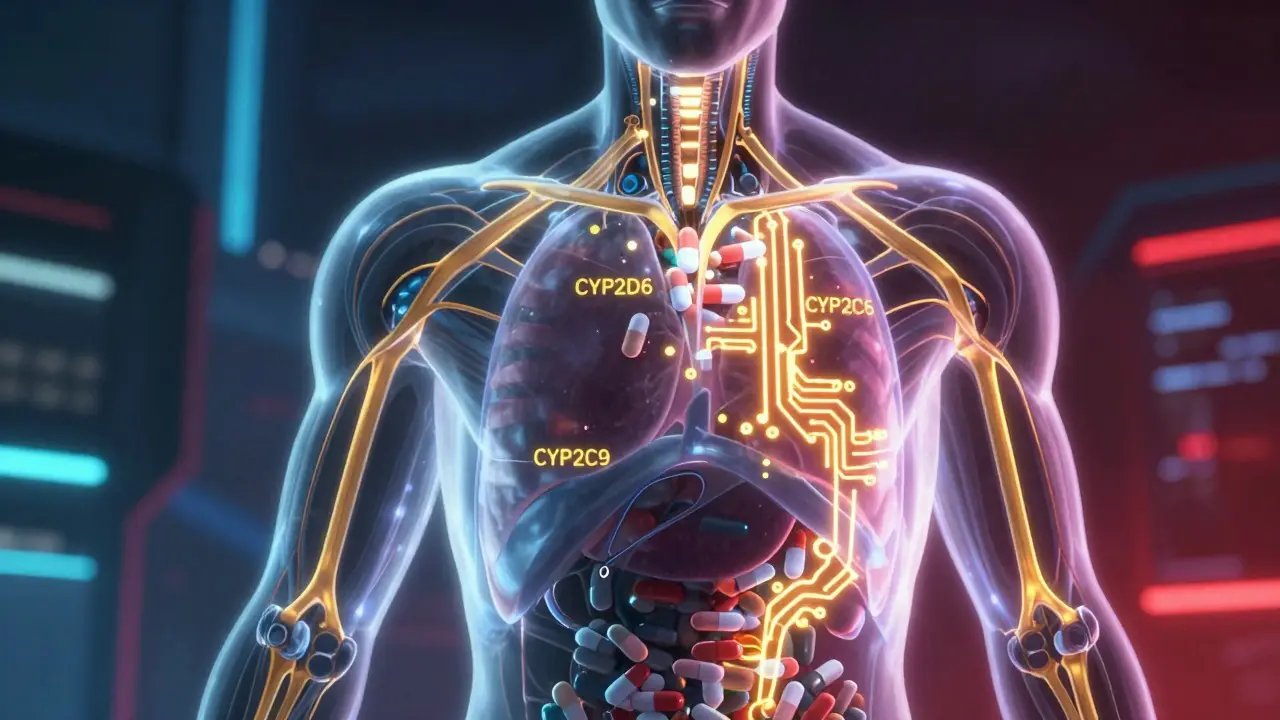

Your DNA decides how fast or slow your body breaks down drugs. The key players are enzymes called cytochrome P450 - especially CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19. These are like little factories in your liver. Some people have versions of these enzymes that work super fast. Others have broken versions that barely work at all. For example, about 5-10% of white Europeans are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6. That means drugs like codeine, antidepressants, or beta-blockers stick around too long. They build up. Side effects spike. On the flip side, 1-2% of Europeans - and up to 29% of Ethiopians - are ultra-rapid metabolizers. Their bodies clear drugs too fast. The medicine doesn’t work. They think it’s ineffective, so they take more. And then - boom - overdose. This isn’t theory. It’s documented. A 68-year-old woman in a JAMA case study kept having dangerous bleeding from warfarin, even though her dose hadn’t changed. Turns out, she had two broken copies of CYP2C9. Her body couldn’t process the drug. Once her doctors knew, they cut her dose by 60%. Her INR stabilized. She went home.Age Changes Everything

As you get older, your body changes - and so do your reactions to drugs. Older adults have more body fat and less muscle. Fat-soluble drugs like benzodiazepines or antidepressants get stored in fat tissue. They linger. That’s why seniors are 3-5 times more likely to have falls from sedatives. Their kidneys and liver don’t filter drugs as well. Even if the dose is “normal,” it’s too much for them. And it’s not just age. If you’re sick with an infection or inflammation, your liver enzymes slow down. That means drugs you’ve taken for years suddenly become stronger. A simple cold can turn a safe dose into a dangerous one.

Drug Interactions Are Silent Killers

Taking two pills together can be like mixing chemicals. Amiodarone - a heart rhythm drug - blocks the enzyme that breaks down warfarin. That can double or even triple warfarin levels in your blood. Result? Uncontrolled bleeding. NSAIDs like ibuprofen are fine for most people. But if you have a certain gene variant and take steroids at the same time? Your risk of a stomach bleed jumps from 1-2% to 15-30%. Polypharmacy - taking five or more medications - is the biggest risk factor for ADRs in older adults. One study found these patients have ADR rates 300% higher than younger people. It’s not the drugs alone. It’s the combinations. And most doctors don’t check for them.Pharmacogenomics: The Future Is Here (But Not Everywhere)

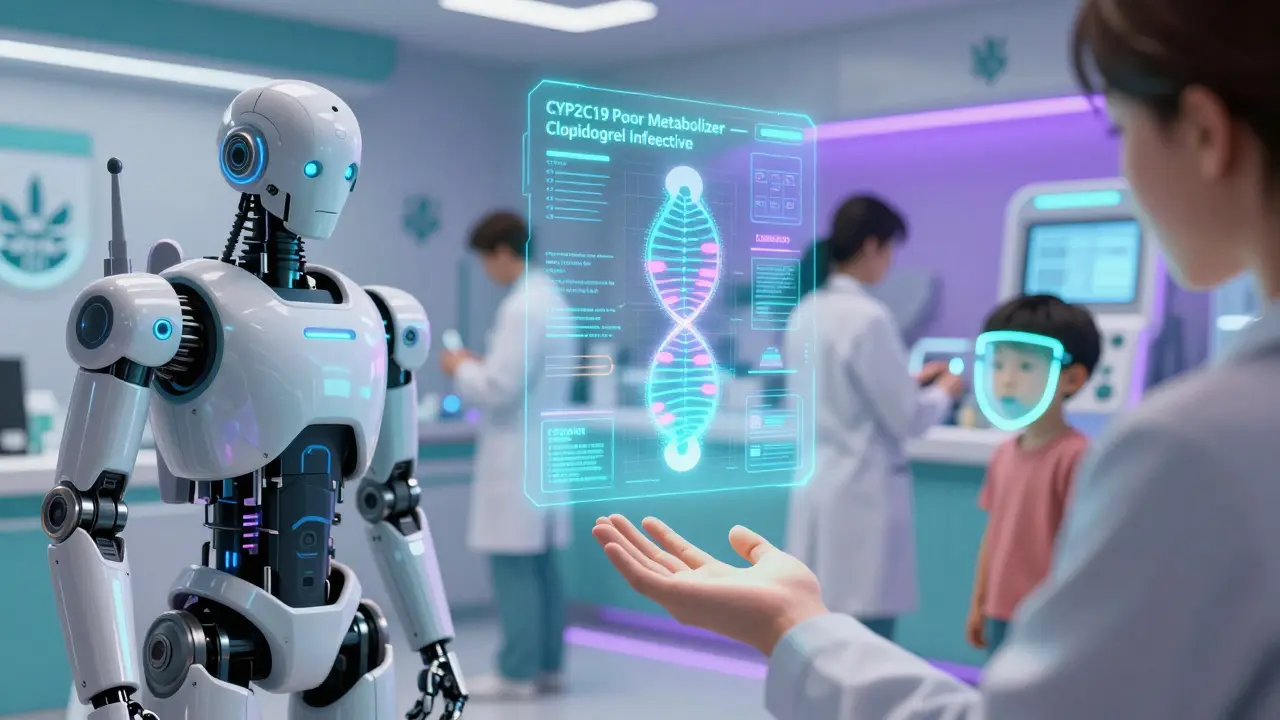

There’s a solution: pharmacogenomics. That’s just a fancy word for using your genes to pick the right drug and dose. The FDA has included genetic info on over 300 drug labels. For 44 of them, they give specific dosing advice based on genetics. Take clopidogrel. It’s a common blood thinner after a heart attack. But if you’re a poor metabolizer of CYP2C19 - 2-15% of people - the drug doesn’t work. You’re still at risk of a clot. Testing for this variant could save lives. Yet, it’s still not routine in most hospitals. Warfarin is another win. Genetic testing for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 explains 30-50% of why people need different doses. In trials, patients who got genotype-guided dosing reached safe levels faster and had 31% fewer major bleeds. In pediatric cancer, St. Jude’s Hospital cut severe side effects from mercaptopurine by more than half using genetic testing. That’s not a small win. That’s life-changing.

Why Isn’t Everyone Getting Tested?

Because it’s still not easy. Only 18% of U.S. insurers cover pharmacogenomic tests. Most doctors haven’t been trained to read the reports. A 2023 survey found 68% of physicians feel unprepared to use genetic data. Hospitals lack the systems to automatically flag risky gene-drug combinations in electronic records. The cost used to be $2,000 per test. Now it’s down to $250. That’s cheaper than a month’s supply of many prescriptions. But the biggest barrier? Doctors don’t ask. They don’t know what to ask. And patients don’t know to ask for it.What Can You Do?

You don’t need a genetic test to protect yourself. Start here:- Know your meds. Keep a list - including over-the-counter drugs and supplements.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Could this interact with anything else I’m taking?”

- If you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug before, tell your doctor. Don’t just say “it made me sick.” Say: “I got dizzy after taking X. I stopped it.”

- If you’re on long-term meds like warfarin, clopidogrel, or antidepressants, ask: “Is there a genetic test that could help me get the right dose?”

- If you’re over 65, ask if your dose is too high for your age.

The Bigger Picture

The future isn’t just about one gene. It’s about hundreds. New tools called polygenic risk scores are starting to combine dozens - even hundreds - of genetic signals to predict how you’ll respond to a drug. Early results show they’re 40-60% more accurate than single-gene tests. The U.S. Medicare system just started covering pharmacogenomic testing for 17 high-risk drugs in January 2024. The EU now requires genetic data in all new clinical trials. Academic hospitals are building programs. The market is growing fast - from $5 billion in 2022 to an expected $24 billion by 2029. But technology alone won’t fix this. We need doctors who understand genetics. We need systems that warn before a bad mix happens. We need patients who speak up. Medications aren’t one-size-fits-all. They never were. The sooner we accept that, the fewer people will get hurt by the very things meant to heal them.Why do some people get side effects from a drug while others don’t?

It’s mostly due to genetics. Your genes control how your body absorbs, breaks down, and responds to drugs. For example, variations in CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 enzymes can make you a slow or fast metabolizer, causing drugs to build up or wear off too quickly. Age, other medications, liver or kidney function, and even infections can also change how your body handles medicine.

Is pharmacogenomic testing worth it?

For certain drugs, yes. If you’re taking warfarin, clopidogrel, certain antidepressants, or chemotherapy drugs like mercaptopurine, genetic testing can prevent serious side effects or help find the right dose faster. Studies show it reduces hospitalizations and bleeding events. For most people on simple medications, it’s not yet essential - but it’s becoming more accessible and affordable, with tests now under $250.

Can I get genetic testing for drug reactions through the NHS?

Currently, routine pharmacogenomic testing isn’t standard in the NHS. It’s mostly used in specialized settings like cancer care or cardiology. But that’s changing. With Medicare in the U.S. covering testing for 17 drugs in 2024, pressure is growing for similar coverage in the UK. If you’re on a high-risk medication and have had a bad reaction, ask your doctor about referral to a pharmacogenomics clinic.

What drugs are most likely to cause genetic-related side effects?

Warfarin (blood thinner), clopidogrel (antiplatelet), certain antidepressants like SSRIs and TCAs, statins (cholesterol drugs), codeine and other opioids, and chemotherapy agents like 6-mercaptopurine. The FDA has labeled over 300 drugs with pharmacogenomic information. If you’re on long-term treatment for heart disease, depression, or cancer, ask if your drug is on the list.

Does having a family history of bad drug reactions mean I’ll have them too?

It’s a strong clue. If your parent had a severe reaction to a drug like codeine or warfarin, you may carry the same gene variant. It doesn’t guarantee you’ll react the same way - other factors like age and other meds matter - but it’s a red flag. Tell your doctor. It could save you from a dangerous reaction.

Are over-the-counter drugs safe if they’re not prescription?

Not necessarily. NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen cause stomach bleeds in 1-2% of users each year - but that risk jumps dramatically if you have certain genes or take steroids. Even common supplements like St. John’s Wort can interfere with antidepressants or birth control. Just because it’s sold without a prescription doesn’t mean it’s risk-free.