When a life-saving drug runs out, who gets it? This isn’t a dystopian fiction scenario-it’s happening right now in hospitals across the U.S. and the U.K. In 2023, the FDA listed 319 active drug shortages, with cancer drugs like carboplatin and cisplatin hitting critical lows. For oncologists, this isn’t just a supply chain problem-it’s a daily moral test. One nurse in Manchester told me, "I had to tell two patients I couldn’t give them their next dose because the hospital ran out. Neither knew why. Neither got a choice." This is the reality of rationing medications: when there’s not enough to go around, someone has to decide who gets treated-and who doesn’t. And those decisions aren’t made on the fly. They’re supposed to follow strict ethical frameworks. But in practice? Too often, they’re not.

What Exactly Is Medication Rationing?

Medication rationing isn’t about hoarding or price gouging. It’s the formal, systematic process of distributing limited drugs when demand outstrips supply. It happens when a manufacturer can’t produce enough, a raw material runs out, or a plant shuts down. In 2011, there were 61 drug shortages in the U.S. By 2023, that number had jumped to 319. Sterile injectables-especially cancer, anesthesia, and antibiotic drugs-are the most affected. One study found that 70% of U.S. cancer centers faced severe shortages of key chemotherapy drugs between March and August 2023. Rationing isn’t about running out of pills. It’s about having enough for 60% of patients, not 100%. And when that happens, doctors aren’t supposed to flip a coin. They’re supposed to use a plan.The Ethical Frameworks That Should Guide Decisions

There are three main ethical frameworks used to make these calls. They’re not just theory-they’re written into guidelines by major medical organizations. The first is the Daniels and Sabin Accountability Framework. It says any rationing decision must be:- Public-patients and staff should know how decisions are made

- Based on evidence-not gut feelings or hospital politics

- Appealable-if you’re denied, you can challenge it

- Enforced-someone has to make sure the rules are followed

- A team with pharmacists, nurses, doctors, social workers, ethicists, and even patient advocates

- Clear criteria like "likelihood of benefit" and "urgency of need"

- Transparency with patients-no one should be left in the dark

- How urgent is the need?

- How likely is the patient to benefit?

- How long will the benefit last?

- Who has the most years of life ahead?

- Does the person serve a critical role (like a frontline worker)?

What’s Actually Happening in Hospitals?

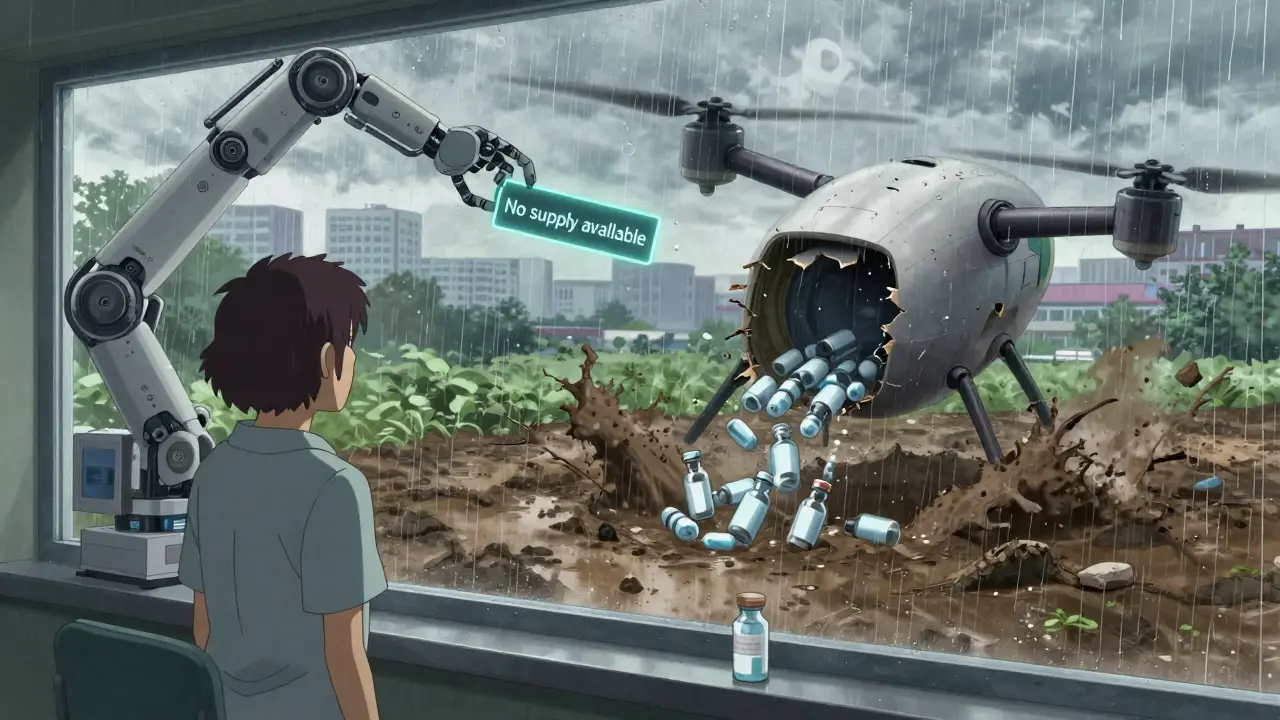

Here’s the gap: the rules exist. The systems exist. But most hospitals aren’t using them. A 2022 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that 51.8% of rationing decisions were made by individual clinicians-no committee, no guidelines, no transparency. That means a nurse or doctor, under pressure, alone, decides who gets the last dose. And that’s not just risky-it’s ethically dangerous. Hospitals with formal committees had 32% fewer disparities in who got treatment. But only 36% of U.S. hospitals even had standing shortage committees in 2018. And of those, just 2.8% included an ethicist. In rural hospitals? 68% had no protocol at all. One oncologist in Minnesota said: "I had to choose between two patients with stage IV ovarian cancer. I picked the one who’d been on treatment longer. I didn’t know if that was fair. No one told me how to decide."

Who Gets Left Out?

The biggest failure in current systems? Equity. A 2021 report from the Hastings Center found that 78% of rationing protocols don’t include any specific measures to protect marginalized groups. That means people of color, low-income patients, or those without strong advocates are more likely to be denied care. And it’s not just about race or income. It’s about access. Academic hospitals with big pharmacy departments can stockpile drugs. Community clinics? They get what’s left. In 2023, 87% of community oncology practices reported severe shortages. Only 63% of academic centers did. Patients are rarely told what’s happening. Only 36% of affected patients were informed about rationing, according to JAMA. Some never find out. Others only learn when they’re turned away.How Do Hospitals Actually Set Up a Fair System?

The good news? We know what works. The Minnesota Department of Health published a clear, step-by-step guide for carboplatin and cisplatin rationing in April 2023. It breaks patients into tiers:- Tier 1: Curative intent, no alternative drug available

- Tier 2: Palliative intent, but survival benefit is clear

- Tier 3: Maintenance therapy, where delay is less critical

- Using the lowest effective dose at the longest possible interval

- Documenting every decision in the electronic health record

- Training staff on ethics and communication

- Conservation: Use less per dose, stretch out intervals

- Substitution: Switch to a similar, available drug

- Rationing: Only if the above fail-then use the committee

Why Don’t More Hospitals Do This?

Because it’s hard. Setting up a committee takes 90 days minimum. Doctors resist. Budgets are tight. Leadership doesn’t prioritize ethics until a crisis hits. One hospital leader told a 2022 survey: "We knew we should have a committee. But we were too busy. Then we ran out of cisplatin. Three patients died waiting. Now we’re scrambling." The biggest barrier? Time. Committee decisions take 14 to 72 hours. In an emergency, that’s too long. But bedside decisions? They’re faster-and far more damaging.

What’s Changing?

There’s hope. In May 2023, ASCO launched an online rationing decision support tool-free, public, and built on the 2023 guidelines. It walks clinicians through real-time scenarios. The FDA is building an AI-powered early warning system, aiming to cut shortage duration by 30% by 2025. And in January 2024, the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities began pilot certification programs for hospital ethics committees in 15 states. Hospitals that pass get a seal of approval. These aren’t magic fixes. But they’re steps toward consistency.What Patients and Families Should Know

If you or a loved one is on a drug that’s in short supply:- Ask: "Is there a rationing system here?"

- Ask: "Who decides who gets the drug?"

- Ask: "Will I be told if I’m not getting it?"