When your liver stops working, there’s no backup. No second chance. That’s why liver transplantation isn’t just a surgery-it’s a second life. For people with end-stage liver disease, it’s the only real option left. Around 8,000 people in the U.S. get a new liver every year. In the UK, numbers are lower but rising, especially as fatty liver disease becomes more common. Survival rates are strong: 85% make it past one year, and 70% are still going strong five years later. But getting there? It’s not simple. It’s a long road with strict rules, complex surgery, and lifelong medication. Here’s what you actually need to know.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant? It’s Not Just About Being Sick

You can’t just sign up for a liver transplant because you have cirrhosis or hepatitis. There’s a system. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, or MELD score, decides who gets priority. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The higher the score, the sicker you are. Scores range from 6 to 40. Someone with a MELD of 35 is in critical condition-they’re likely to die within three months without a transplant. Someone with a MELD of 10 might wait years.

But the MELD score isn’t the whole story. You also need to pass a psychosocial evaluation. Are you stable at home? Do you have someone to help you after surgery? Have you stopped drinking or using drugs? Many transplant centers require six months of sobriety before listing. But here’s the catch-not all centers agree. Some now accept three months if you’re in counseling and have strong support. In British Columbia, they’ve even started adjusting rules for Indigenous patients, adding cultural support to the evaluation. It’s not just about your liver-it’s about your whole life.

There are hard no’s too. If you have active cancer that’s spread beyond the liver, you’re not eligible. If you have severe heart or lung disease that can’t be fixed, you won’t be listed. And if you’re still using alcohol or illegal drugs? You’re off the list until you prove you’ve changed.

Living Donor vs. Deceased Donor: What’s the Difference?

You can get a liver from someone who’s died-or from someone who’s still alive. About 1 in 5 liver transplants in the U.S. come from living donors. In the UK, it’s less common, but growing. The donor gives part of their liver-usually the right lobe, which is about 60% of the organ. Their liver regrows. Yours grows too. Within a few months, both livers are back to normal size.

Why choose a living donor? Speed. If you’re on the waiting list for a deceased donor liver, you might wait a year or more. With a living donor, you can schedule the surgery. For someone with a MELD score over 25, that can mean the difference between life and death. But it’s not risk-free. Donors face a 0.2% chance of dying during surgery. About 20-30% have complications like bile leaks or infections. Recovery takes 6 to 8 weeks. Most return to work by 3 months.

Deceased donor livers come from two sources: donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD). DCD livers used to have higher complication rates-especially bile duct problems. But now, new machines that keep the liver alive outside the body (called machine perfusion) have cut those risks by nearly a third. Some centers, like UPMC in Pittsburgh, now use these machines for nearly all DCD livers. That’s a big win.

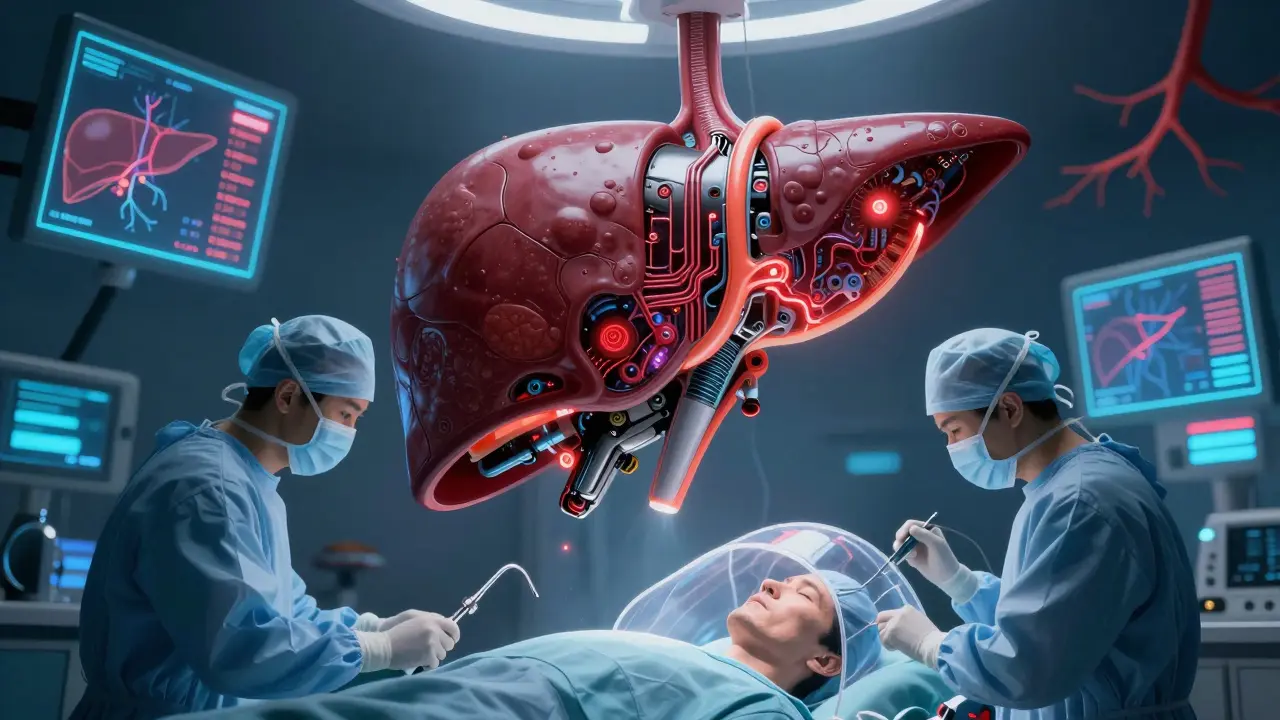

The Surgery: What Happens During the Operation

A liver transplant takes 6 to 12 hours. The surgeon removes your damaged liver, waits for the new one to arrive, then connects it to your blood vessels and bile ducts. Most of the time, they use something called the piggyback technique. That means they leave your inferior vena cava-the big vein that carries blood back to your heart-in place. It makes the surgery easier and lowers the risk of bleeding.

After your old liver is out, you enter the anhepatic phase. No liver. No detox. No clotting. No bile production. Your body survives on machines and IV fluids. It’s tense. The new liver is stitched in. Blood flow is restored. And then-you wait. Does it start working? Does it make bile? Are the veins clear? If everything looks good, you’re out of the danger zone.

After surgery, you spend 5 to 7 days in intensive care. Total hospital stay is usually 2 weeks. You’ll be on oxygen, monitors, IV drips, and pain meds. You’ll be weak. You’ll be scared. But you’ll also be alive.

Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Price of a New Liver

Your body doesn’t know your new liver isn’t yours. It sees it as an invader. So you take drugs to stop your immune system from attacking it. This is called immunosuppression. And it’s not optional. Skip a dose? Risk rejection. Take too much? Risk infection or cancer.

The standard combo is three drugs: tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. Doctors keep your blood level between 5 and 10 ng/mL in the first year. After that, they lower it to 4-8. Mycophenolate stops white blood cells from multiplying. Prednisone is a steroid-used to calm inflammation early on. But here’s the good news: 45% of U.S. transplant centers now skip prednisone after the first month. Why? Because it causes diabetes, weight gain, and bone loss. Cutting it out cuts diabetes risk from 28% to 17%.

Side effects are real. One in three people on tacrolimus develop kidney damage after five years. One in four get diabetes. One in five get shaky hands or headaches. Mycophenolate causes nausea and diarrhea in 30% of patients. It can also lower your white blood cell count, making you more prone to infections.

Every three months, you’ll have blood tests to check your drug levels. Every six months, you’ll get a liver biopsy to look for early signs of rejection. If your body starts attacking the new liver, doctors will bump up your tacrolimus dose or add sirolimus. About 15% of patients need this kind of adjustment in the first year.

What Happens After You Go Home?

You’ll need to take your meds at the exact same time every day. Miss even one dose in the first few months? That’s enough to trigger rejection. You’ll track your temperature. If it hits 100.4°F or higher, you call your transplant team. Jaundice? Dark urine? Abdominal swelling? Those are red flags. You can’t wait and see.

You’ll have weekly blood tests for the first three months. Then biweekly. Then monthly. After a year, you’ll be tested every three months. You’ll also need to avoid grapefruit-it interferes with tacrolimus. You’ll need to skip live vaccines. You’ll be told to wash your hands constantly, avoid crowds during flu season, and never eat raw shellfish.

The cost? Around $25,000 to $30,000 a year just for meds. That doesn’t include doctor visits, lab tests, or hospital stays for complications. Insurance often covers most of it, but 32% of patients say they were denied coverage for pre-transplant evaluations. That’s a huge barrier.

And you need support. Transplant centers with dedicated coordinators have 87% one-year survival rates. Those without? Only 82%. That’s not a small gap. It’s life or death.

What’s Changing? New Rules, New Tech

The field is moving fast. In 2023, the FDA approved a portable liver perfusion device called Liver Assist. It keeps donor livers alive for up to 24 hours instead of 12. That means organs can travel farther. More people get matched. Fewer livers go to waste.

Research is also looking at whether some patients can stop immunosuppression entirely. At the University of Chicago, 25% of kids who got liver transplants were able to stop all drugs by age 5. They used a special therapy to train the immune system to accept the new liver. It’s still experimental, but it’s the first real hope for freedom from lifelong meds.

Eligibility rules are changing too. The AASLD now allows donors with controlled high blood pressure and BMI up to 32. That’s a big shift. Before, even mild obesity or hypertension disqualified people. Now, centers are learning that with careful selection, outcomes are just as good.

And for liver cancer? The Milan criteria still apply: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. But if your tumor is bigger and you’ve had treatment, you might still qualify-if your tumor shrinks enough and stays stable for six months. That’s new. And it’s giving more people a shot.

It’s Not Perfect. But It Works.

Liver transplantation isn’t a cure-all. It’s a trade-off. You get life-but you trade it for daily pills, constant checkups, and fear of rejection. You get a second chance-but you owe it to your donor, your team, and yourself to take care of it.

For many, it’s the only way out. One woman in Manchester, diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis, was told she’d die within a year. She quit drinking. Got therapy. Got listed. Got a liver. Five years later, she’s hiking in the Peak District. She takes her pills. She sees her team. She doesn’t take it for granted.

That’s what this is. Not magic. Not a miracle. Just hard work, science, and a lot of courage-from donors, patients, and doctors alike.

Can I get a liver transplant if I used to drink alcohol?

Yes, but most centers require at least six months of sobriety before listing. Some now accept three months if you’re in counseling and have strong support. You’ll need to prove you’ve changed through regular meetings with an addiction specialist and consistent negative alcohol tests. It’s not just about quitting-it’s about showing you can stay quit.

How long do I wait for a liver transplant?

It depends on your MELD score and where you live. In high-MELD patients (scores above 25), the average wait is 12 months for a deceased donor liver. But in some regions, like California, you might wait 18 months. With a living donor, you can skip the wait entirely-surgery can happen in as little as 3 months. Geographic disparities are real: patients in the Midwest often get transplants faster than those on the West Coast.

What are the biggest risks after a liver transplant?

The biggest risks are rejection, infection, and side effects from immunosuppressants. Rejection can happen anytime, but most cases occur in the first year. Infections are common because your immune system is suppressed. Long-term, you’re at higher risk for kidney damage, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers. That’s why lifelong monitoring is non-negotiable.

Can I have children after a liver transplant?

Yes. Many people have healthy pregnancies after transplant. But it’s not recommended until at least one year after surgery, and only if your liver function is stable and your immunosuppression is well-controlled. You’ll need close monitoring by both your transplant team and an obstetrician. Some medications, like mycophenolate, must be switched before pregnancy because they can cause birth defects.

Do I need to change my diet after a liver transplant?

Yes. You need to avoid grapefruit, pomegranate, and Seville oranges-they interfere with tacrolimus. Raw seafood, undercooked meat, and unpasteurized dairy increase infection risk. You’ll need to eat lean protein, vegetables, and whole grains to support healing and prevent weight gain from steroids. Many centers provide a dietitian as part of your care team.

What if my new liver fails?

If the new liver fails due to rejection, infection, or other complications, you may be eligible for a second transplant. It’s rare-only about 5-10% of recipients need one. But it’s possible. The criteria are stricter, and survival rates are lower than for first transplants. Still, many people live for years after a second transplant, especially if the failure happens late.