Switching from a brand-name drug to a generic version seems like a simple way to save money. But for a small group of medications called NTI drugs, that switch can be risky-sometimes life-threatening. These aren’t ordinary pills. They’re drugs where the difference between working properly and causing serious harm is razor-thin. Even a tiny change in how much of the drug enters your bloodstream can push you from safe to dangerous.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

NTI stands for Narrow Therapeutic Index. That means the gap between the dose that helps you and the dose that hurts you is very small. For most medicines, your body can handle a bit more or less without consequence. But with NTI drugs, a 10% increase in blood levels might cause toxicity. A 10% drop might mean the drug stops working.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration defines NTI drugs as those where small changes in dose or blood concentration can lead to serious therapeutic failures or adverse reactions. Examples include warfarin (a blood thinner), phenytoin (an anti-seizure drug), lithium (for bipolar disorder), digoxin (for heart failure), and methadone (for pain or addiction). These drugs don’t just need to work-they need to work within a tight window. For warfarin, the target is an INR between 2.0 and 3.0. Go above 3.0, and you risk bleeding. Drop below 2.0, and you could get a clot.

Why Generic Substitution Is Problematic

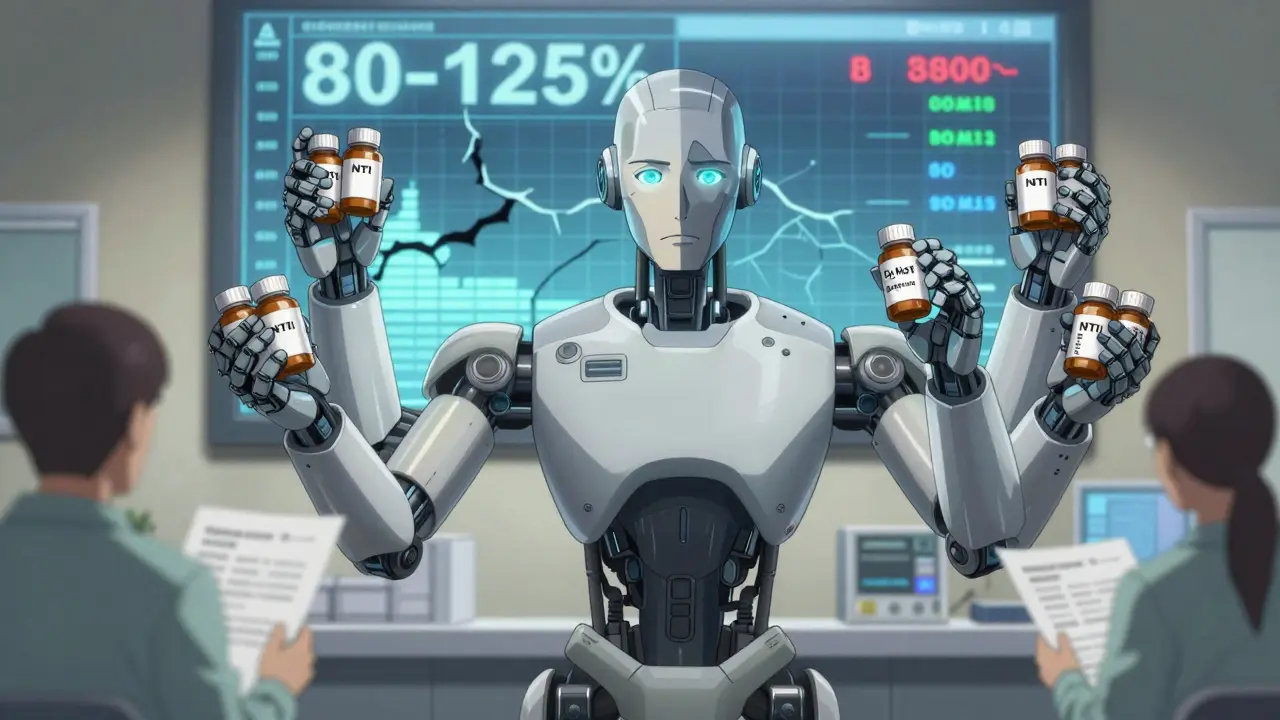

The FDA requires generic drugs to be bioequivalent to the brand-name version. That means their absorption rate must fall within 80% to 125% of the original. Sounds reasonable, right? But for NTI drugs, that 45% range is too wide. If the brand drug gives you a blood level of 15 mcg/mL, the generic could legally be anywhere from 12 to 18.75 mcg/mL. For phenytoin, the safe range is 10 to 20 mcg/mL. A shift from 15 to 18.75 could mean toxicity-nystagmus, dizziness, even coma.

It’s not just about the active ingredient. Generic versions can differ in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing processes. These differences affect how the drug dissolves and gets absorbed. One patient might switch from brand-name Coumadin to generic warfarin and have no issues. Another might have their INR spike or crash within days. There’s no way to predict who will be affected.

Real-World Consequences

There are documented cases of patients suffering after switching. In the 1980s, people on phenytoin started having breakthrough seizures after their pharmacy switched them to a generic version. In another case, a patient on methadone for chronic pain was switched to a generic with slightly higher bioavailability. Within hours, they developed respiratory depression-enough to require emergency care. These aren’t rare anomalies. They’re predictable outcomes of a system that treats all drugs the same.

Warfarin is the most studied. Some studies say generic warfarin is safe. Others show clear spikes in INR levels after switching, even when patients stayed on the same dose. One study found patients switching from Coumadin to generic warfarin needed more frequent blood tests and had higher rates of hospitalization due to bleeding or clotting. The American Medical Association says it clearly: the prescribing doctor should decide whether to allow substitution-not the pharmacist, not the insurance company.

Who Decides? The Medical Divide

The FDA maintains that approved generics are therapeutically equivalent to brand-name drugs. But many doctors, pharmacists, and patients don’t agree. A 2019 survey of pharmacists showed that while most trusted generics overall, those working outside big chain pharmacies were more skeptical about NTI drugs. Female pharmacists, in particular, expressed more concern.

Some experts go further. They argue that generic substitution for NTI drugs should be banned outright. The logic is simple: if the margin for error is two-to-one, then a 25% variation in absorption isn’t just a technicality-it’s a safety failure. The North Carolina Board of Pharmacy explicitly defines NTI drugs as those with “limited or erratic absorption” and says they require blood-level monitoring. That’s not something you can trust to a pharmacy’s automated substitution system.

What Patients Need to Know

If you’re on an NTI drug, don’t assume your pharmacist’s switch is harmless. You have the right to ask: “Is this the same brand I’ve been taking?” If you’re switched without your knowledge, monitor yourself closely. For warfarin, watch for unusual bruising, nosebleeds, or dark stools. For phenytoin, look for unsteady walking, slurred speech, or confusion. For lithium, check for hand tremors, frequent urination, or nausea.

Keep a written list of all your medications-including the brand or generic name and dose-and share it with every provider. Don’t let anyone guess what you’re on. Ask your doctor to write “Dispense as written” or “Do not substitute” on your prescription. Most states allow this. In some, like North Carolina, automatic substitution for NTI drugs is already restricted by law.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about one drug or one patient. About 15 to 20% of commonly prescribed medications are NTI drugs. That’s millions of people on warfarin, lithium, or epilepsy meds. The push for generics comes from cost pressures-insurance companies, pharmacies, and government programs want to cut expenses. But when safety is on the line, savings shouldn’t come at the cost of harm.

The FDA has acknowledged the issue and recommends tighter bioequivalence standards for NTI drugs. But no official changes have been made yet. Until then, the burden falls on patients and prescribers to stay vigilant. There’s no national database that flags NTI drugs at the pharmacy counter. No warning label. No automated alert. You have to know what you’re on-and speak up.

What’s Next?

Experts are calling for more research. The American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics wants real-world data on the risks of switching NTI drugs. Some are pushing for therapeutic drug monitoring to become routine for patients on these meds. Others suggest that generics for NTI drugs should be required to match the brand within a tighter range-say, 90% to 111%-instead of the current 80% to 125%.

Until those changes happen, the safest approach is simple: if you’re on an NTI drug, don’t let anyone switch it without your doctor’s approval. Keep your dose consistent. Track your symptoms. Ask questions. Your life may depend on it.

Are all generic drugs unsafe?

No. Most generic drugs are just as safe and effective as brand-name versions. The issue only applies to drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, phenytoin, lithium, digoxin, and methadone. For antibiotics, blood pressure pills, or antidepressants, switching generics is usually fine. The risk is specific to medications where small changes in blood levels can cause serious harm.

Can my pharmacist switch my NTI drug without telling me?

In many states, yes-unless your doctor writes "Dispense as written" or "Do not substitute" on the prescription. Automatic substitution laws allow pharmacies to swap generics unless explicitly prohibited. That’s why it’s critical to ask your pharmacist what version you’re getting and to confirm with your doctor if the switch was intentional.

What should I do if I notice side effects after switching to a generic?

Don’t ignore it. Contact your doctor immediately. For warfarin, request an INR test. For phenytoin or lithium, ask for a blood level check. Keep a log of symptoms-when they started, how severe they are, and what you were taking before. This information helps your doctor determine if the switch caused the problem and whether you need to go back to the original brand.

Is there a list of NTI drugs I can check?

There isn’t one official list in the U.S., but the FDA and organizations like the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) maintain unofficial lists. Common NTI drugs include warfarin, phenytoin, lithium, digoxin, theophylline, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and methadone. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist or doctor. If your medication requires blood monitoring, it’s likely an NTI drug.

Why doesn’t the FDA change the bioequivalence rules for NTI drugs?

The FDA has acknowledged the issue and recommended tighter standards since at least 2010, but changing regulations is slow. The pharmaceutical industry resists stricter rules because they make generic approval harder and more expensive. Without strong public pressure or new clinical data showing clear harm, change moves slowly. Until then, the current 80-125% range remains the legal standard-even when it’s too wide for safety-critical drugs.